When China Consumes the Future

The Brief: How rising domestic demand for rare earths could erode US competitiveness across the AI stack

“There is oil in the Middle East, and there is rare earth in China”

— Deng Xiaoping (邓小平), 1992

The Situation: The Busan Summit

Presidents Xi Jinping and Donald Trump met in Busan on October 30th and agreed to a one-year suspension of China’s 2023–25 rare-earth export controls.

The pause offers relief rather than resolution. It rests on two assumptions held in Washington: that semiconductor concessions will secure continued access to Chinese rare earths, and that the volume available for export will remain stable. Both assumptions are fragile.

Beijing’s commitment is reversible, and China’s domestic consumption of rare earths is rising faster than upstream refining capacity. Demand from electric vehicles, renewable energy, robotics, physical AI and defence manufacturing is expanding faster than supply. As absorption increases, the exportable surplus shrinks.

The counterfactual, and the focus of this brief, is that exports could decline even without coercive policy, as China keeps more material to feed its own high-value manufacturing base.

The implications extend well beyond mining. They shape US competitiveness across the AI stack: compute, power, connectivity and embodied intelligence.

If China’s increasing domestic demand reduces export capacity, how would that shape US competitiveness in AI?

The Red Line: Modelling China’s REE Demand

How does Chinese export availability evolve under different domestic-demand trajectories?

Boundary conditions

To define the boundary conditions for scenario modelling of China’s rare-earth dynamics we will focus on three variables:

Allied refining ramp-up: how quickly US and its allies scale relative to China’s demand over and above top-line quota increases.

Chinese domestic demand: growth scenarios range from continuation of the status quo (≤5%) to the double digits (10-12%).

Export-quota enforcement: policy lever which determines the export elasticity of what is left.

Risk is defined as access to REE needed for AI development and dominance.

High-risk scenario: absorptive China

Domestic demand grows at 10-12% a year;

export controls remain tight; and

allied refining capacity lags far behind.

If China’s total refined rare-earth output grows by around 3% a year from an estimated 254,000 tonnes in 2024, supply would reach roughly 320,000 tonnes of REE equivalent by 2030. Exports in 2024 were already limited: around 55,000 tonnes (~20% of supply) across 17 minerals.

The constraint tightens sharply if domestic consumption grows faster than refining capacity. Beijing is now directing rare earths into strategic sectors: electric vehicles, renewable-energy systems, permanent-magnet robotics, “physical AI” hardware, and defence applications. Each of these sectors is magnet-intensive and expanding more quickly than upstream mining and refining.

Under this trajectory, exports shrink not because of sanctions or embargoes, but because China extracts more value by keeping materials at home.

The global result is a structural supply squeeze for foreign buyers, spiking prices and entrenched geopolitical leverage.

Medium-risk scenario: managed competition

Medium domestic growth (5-10%);

moderate export controls; and

allied ramp-up at half the rate as Chinese demand growth.

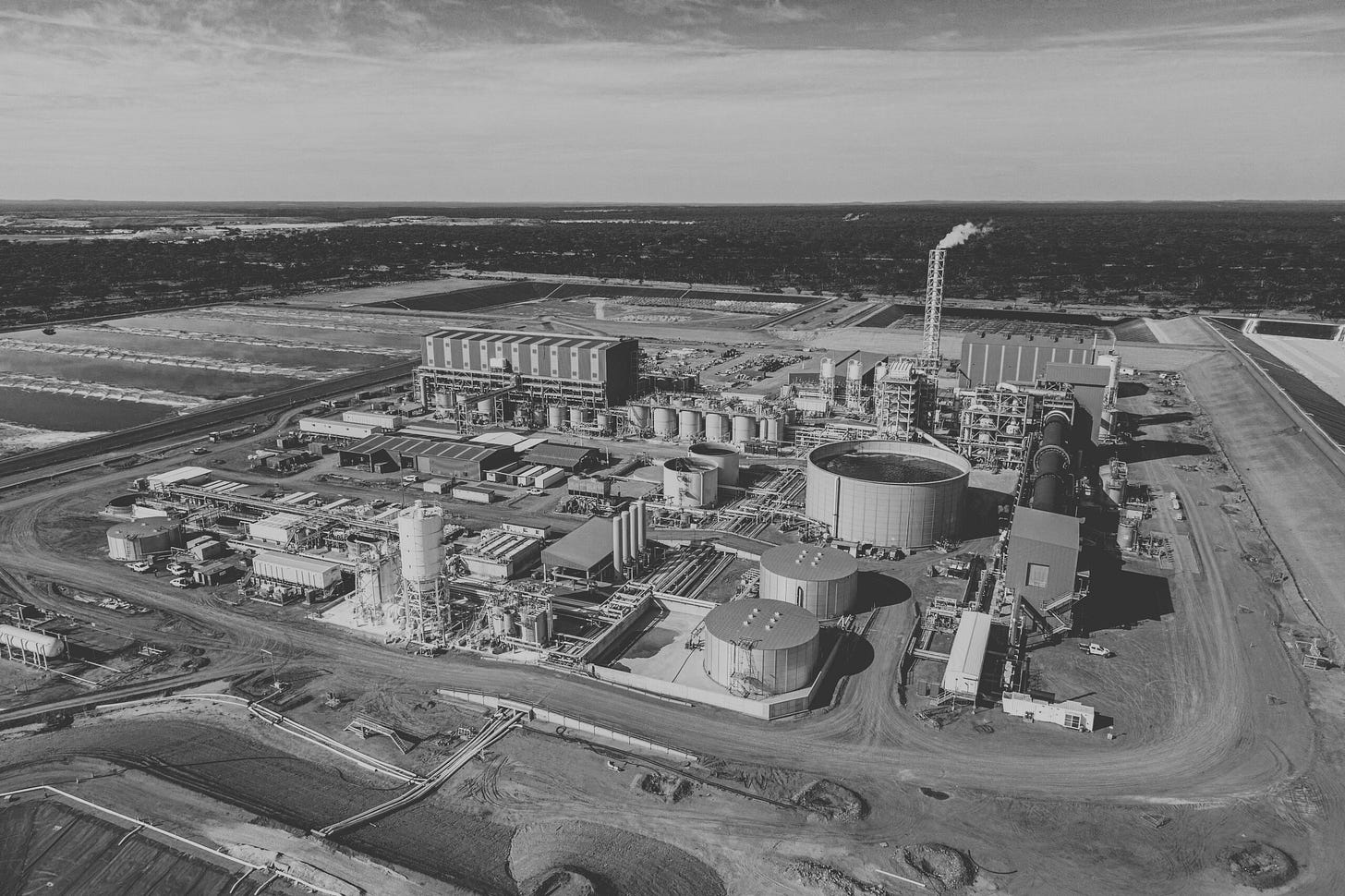

A more balanced trajectory assumes ramp-up by US and allied initiatives, such as MP Materials’ new US processing lines, Canada and Japan’s pilot plants, and Australia’s Kalgoorlie refinery.

In this environment of managed competition, China maintains its cost advantage. China’s refining networks are mature, vertically integrated, and state-supported. Allied output remains higher-cost and vulnerable to cyclical pricing.

The result is reactive policy, punctuated by recurring negotiation rounds that mirror the Busan truce.

Meanwhile, China can continue to use price elasticity as a diplomatic instrument, offering temporary discounts or selective quotas to defuse political pressure. For the US and its allies, sustaining investment in higher-cost refining requires either subsidies or security-of-supply mandates.

Low-risk scenario: overbuild

Low domestic growth (≤5%);

low export controls; and

allied ramp-up on par with Chinese demand growth.

The overbuild scenario could occur if environmental, technological or social constraints limit downstream demand. Under these conditions, global refining capacity exceeds consumption.

The result is a temporary glut: falling prices, excess inventory, and reduced margins for all producers.

Paradoxically, this scenario does not eliminate dependency. Even in an oversupplied market, concentration persists. China would still dominate refining and magnet fabrication.

Rare Earths on the Critical Path to AGI

Where could rare earth exposure become a genuine constraint on the US path to AGI?

Rare-earth elements (REEs) appear on every layer of the AI stack.

Western policy debate often misdiagnoses rare earths as a chipmaking choke point. The real bottleneck lies further downstream.

At the compute layer, REE exposure is critical but tiny.

High-performance processors such as NVIDIA’s B100 and AMD’s MI300 rely on rare earths in their supporting hardware. Neodymium, praseodymium and dysprosium sit in cooling fans and wafer-handling motors; yttrium and lanthanum appear in laser diodes and lithography optics, with trace cerium and europium in polishing and phosphor coatings.

The precision tools that knit the silicon together depend on these materials, but only at the margin. An ASML EUV scanner weighs roughly 180 tonnes and costs about US$200m, yet contains only a few kilograms of rare earths.

Even across an entire fab, the total rare-earth footprint sits in the low hundreds of kilograms, not tonnes.

The US can insulate the compute layer temporarily through stockpiles and priority allocations, especially if allies expand refining capacity with US access in mind. That buys time, but it does not solve the real problem.

AI capability rests on three physical pillars: compute (chips and accelerators), power (energy generation and transmission), and connectivity (data centres and networks). The greater REE risk lies in the last two ingredients.

In the energy and connectivity layers, REE requirements move from grams to tonnes.

The IEA estimates that a typical US data centre draws on a mix of natural gas (40%), renewables (24%), nuclear (20%) and coal (15%). Across these sources, rare-earth intensity increases by orders of magnitude.

The REEs that enable cutting-edge chipmaking would fit inside a suitcase; those that power the grid for AI data centres fill shipping containers.

Wind is the clearest example. A single 10 MW offshore turbine contains 2 to 3 tonnes of neodymium-iron-boron magnets. Supplying even part of a 1 GW data-centre load from wind requires dozens of turbines and tens of tonnes of rare earths. Solar and nuclear use smaller quantities, but in aggregate still impose meaningful, long-lived demand as deployments scale.

Connectivity introduces a second structural exposure. Long-distance fibre networks rely on erbium-doped amplifiers placed every 60 to 100 km along undersea and terrestrial cables. Each unit contains only grams of erbium, but across millions of kilometres of cable this accumulates to tens of tonnes. Local infrastructure adds further pressure: GPU cooling systems and hard-disk drives each use small amounts of magnet material, but across a hyperscale campus this reaches hundreds of kilograms.

Compute, power and connectivity set the conditions to achieve AGI. However, putting AGI to use involves embodied systems, and here rare-earth dependence becomes even more pronounced.

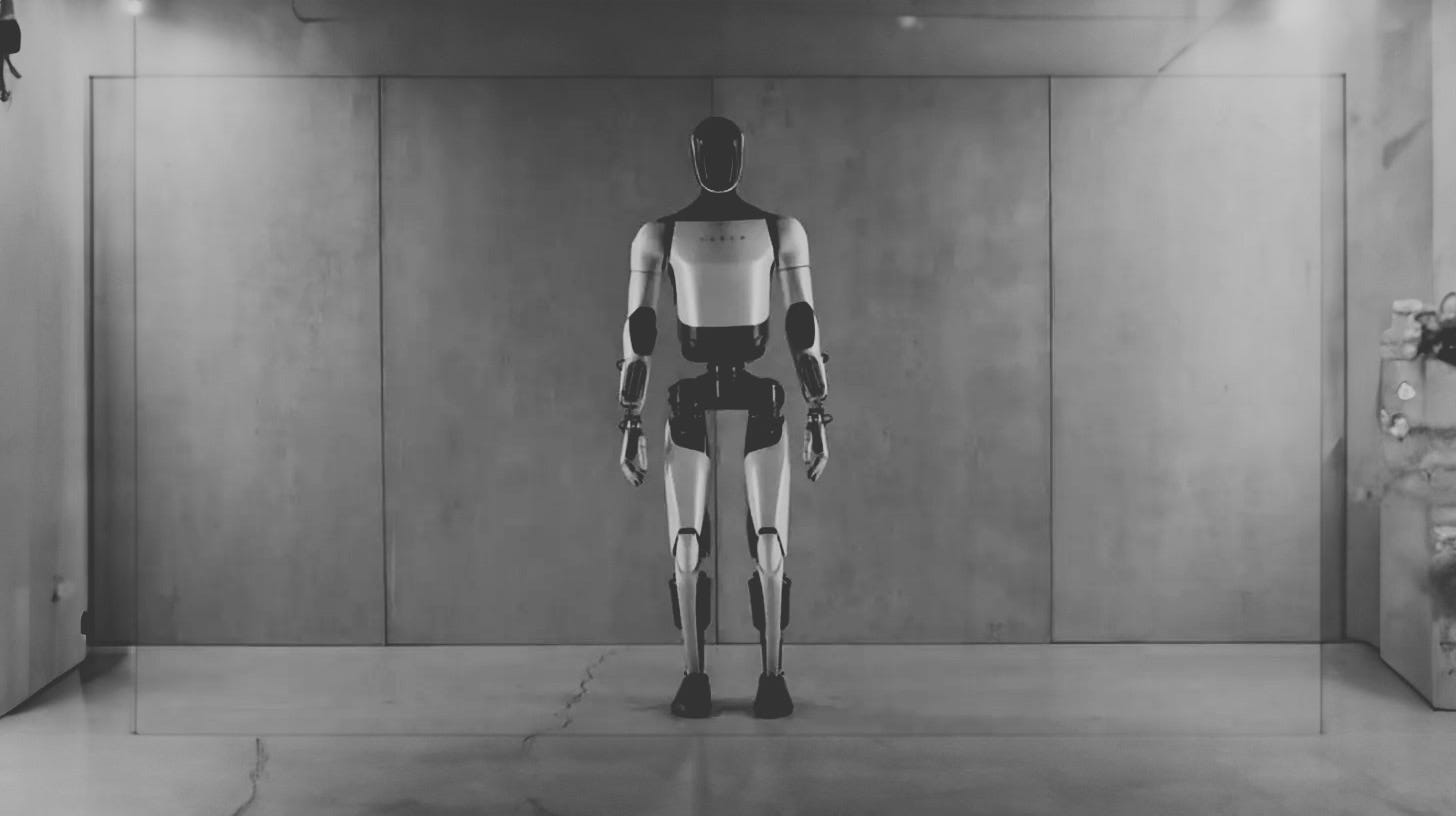

At the embodied AI layer, REE throttling could further extend China’s robotics lead.

Rare earth exposure becomes most strategically consequential in robotics. Unlike the compute layer, embodiment is magnet-intensive. Every actuator, motor and joint depends on neodymium-iron-boron magnets (NdFeB).

China controls roughly 90% of global magnet fabrication, giving Beijing direct leverage over production rates, unit costs and export availability for embodied-AI systems.

Robotics is central to AGI’s usefulness. Embodiment is part of the story of how intelligence becomes economically and militarily useful.

Industrial automation, warehouse logistics, autonomous manufacturing, precision assembly and defence modernisation all depend on physical agents, not just models. Constraints on magnet supply therefore slow the translation of frontier AI into real-world capability. Earlier this year, Chinese magnet export restrictions delayed production of Tesla’s Optimus robot, which contains an estimated 2–4 kg of NdFeB magnets per unit.

According to the International Federation of Robotics, the global operational stock of industrial robots reached 4.6m units in 2024. China alone accounts for more than 2m.

In 2024 China installed 295,000 new units; the US installed 34,200. That is a tenfold gap.

By 2030, US industrial robotics demand is expected to double or triple, but meeting that demand depends on securing reliable access to REE-intensive components. If China prioritises domestic absorption or tightens magnet exports, the US faces a slower and more expensive deployment curve.

Policy failure could give rise to an odd paradox: AI’s disembodied intelligence might be American, but its embodiment will be Chinese.

The Signal: Two Trendlines

Two REE trajectories matter most:

China’s domestic absorption

US diversification and prioritisation

A competitive rare-earth strategy for the US requires four metrics:

supply-adequacy ratio (share of US strategic demand met annually)

cost-escalation factor (price increase vs baseline);

time-to-shortage (years before stockpiles run out);

policy robustness index (% of futures where shortage is avoided).